Best of Budapest & Hungary

Measure of Quality

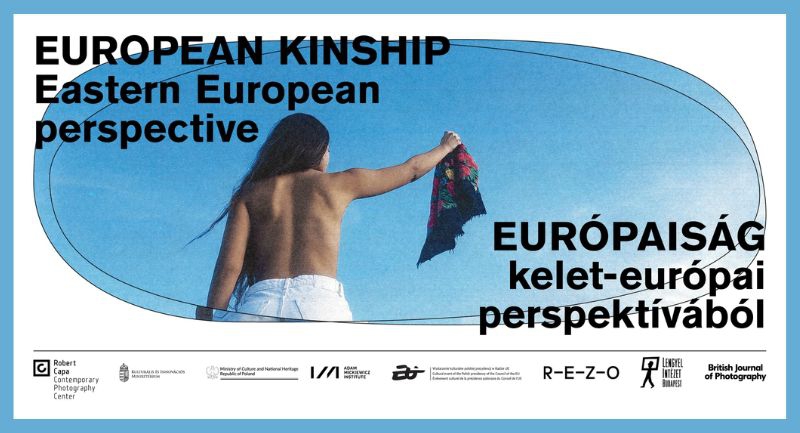

European Kinship – Eastern European Perspective

How can Eastern Europeanism be defined? What is it that is distinctively its own, that binds the peoples who live here and share a common history and geography? And what are the global solutions to local specificities? Or what and how does all this become one in Euro-ness? What are the trends towards deeper European integration and more international cooperation? And how do they affect artistic-photographic practices dealing with the world around us, its phenomena, its effects, and the related feelings and problems? The six-chapter exhibition European Kinship – Eastern European Perspective reflects on European identity through the work of Polish and Hungarian photographers, exploring contemporary experiences from a specifically regional point of view. The exhibition can be visited at the Capa Center until March 30.

Despite the differences between these geographical regions, there is much that connects them. They share common historical roots, having once been part of large empires and being torn apart by wars and conflicts. Throughout history, changing rules and regimes have consistently compelled them to redefine their identities. They are also connected by their diverse ethnic and cultural background, which has served as a driving force for progress in times of peace and a tragically recurring flashpoint during conflicts–a past that has largely been passed down through individual experiences, fragments of collective memory, traces of history, artifacts, and aesthetic references.

Inspired by the regionally shared sense of a breaking point, the chapter entitled ‘Transition’ explores meta-narratives, the archive of collective memory that defined the region’s identity – understood as a mutually felt sentiment rather than a term in an academic glossary – as expressed in the works of two collectives, Sputnik Photos (‘Lost Territories’) and Pictorial Collective (‘Residents of People Living in The Streets Named After The Poet, Sándor Petőfi’). The subsequent chapters, ‘Space’ and ‘Identity’ are dedicated to the material and symbolic representations of political narratives concerning control, power, and emancipation as spatial and architectural metaphors as seen in the works by Katerina Kouzmitscheva (‘BETONIUM’) and Julia Standovar (‘Kinky Concrete’). The themes are also examined through the performative projects on body politics in the performative projects by Ilona Szwarc (‘I Am a Woman and I Feast on Memory’) and Anita Horváth (‘You Are Not Like Them’). The chapter ‘Spirituality’ addresses artistic responses to the emblematic social phenomena related to religion and politics (Agnieszka Sejud’s ‘HOAX’, and Zsuzsi Simon’s ‘And Yet We Still Keep on Living’). Meanwhile ‘Grotesque’ examines the issues of ideology and resistance expressed through peculiarly Eastern European absurdism and irony, represented by Ada Zielińska’s ‘Pyromaniac’s Manual’, and Szabolcs Barakonyi’s ‘Fine, Thanks’. Finally, the chapter ‘Post-Nostalgia’ offers a cavalcade of creativity rooted in the feeling of limitlessness, representing a nonchalant and bold experimentation with the artifacts of new realities in the projects ‘Made in Poland’ by Karolina Wojtas and Éva Szombat’s ‘Echo in Delirium’.

European Kinship explores many complicated social and political themes, but running through it are questions of commonality and shared experience in this region.